In 1968, when I first entered the Philippine Science High School, our science textbooks and even books in the school library were not very strong on astronomy.

But my older brother, Kuya Obet, an avowed astronomy fanatic who was then in his graduating year at the same high school, more than made up for the apparent lack of school books on the subject by buying what his monthly scholar stipend could afford.

And boy, did he splurge on science magazines and cheap science pocketbooks of all kinds. (I of course, devoured them too.) We also frequented the house of our Abra kin in Masambong, Frisco QC (auntie Isabel Bersamin, her scientist-niece Willie Borillo, and other nephews and nieces), with whom we were very close.

Their sizeable library of science books and magazines—Manang Willie’s collection of Scientific American spanned the 1950s and 1960s—was an added incentive for us to visit and stay for hours, especially during weekends and summers.

Whatever we felt still lacking, our parents made up for it by buying more science books—such as the LIFE Nature Library series of books. We kids mercilessly squeezed whatever value they had for us until their covers and pages became miserably loose, brittle and dog-eared. I still have some of them. Also, I still have the 1968 edition of Encyclopaedia Britannica, which my parents bought for me, and for which I incrementally paid via installments c/o my monthly stipend.

Kuya Obet went on to become an activist, political prisoner, hotshot engineer-programmer, and environmentalist. But he never lost his boundless interest and enthusiasm for astronomy and its sister, astrophysics. His library was huge, and I would dive into his science books and magazines as frequently and as extensively as I could. (I still sometimes do, like recently when his son was sorting through Kuya’s massive accumulation of stuff.)

All these are not really a digression on this topic of pulsars. Kuya Obet and I learned about quasars and pulsars and the Gemini-Apollo space programs, etc. through these science magazines in the 1960s even before they entered into our textbooks.

Kuya Obet could have been oh maybe a NASA engineer, or some California-based star-hunter or SETI researcher, had not his activism and family urged him to remain solidly grounded on native soil.

I myself am still grossly fascinated to this day, nay, obsessed, with the universe and its endless celestial objects. And yes, especially about the by-products of supernovae such as black holes (including those with quasar shells), neutron stars (aka pulsars), and life itself (aka stardust).

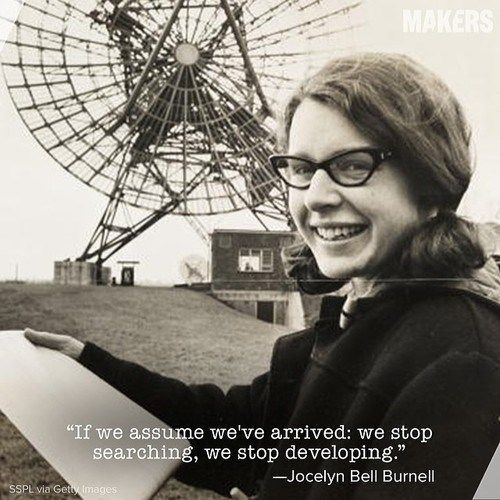

Bottom line: I never realized that it was actually a woman doctoral student named Jocelyn Bell who discovered pulsars. Which means that actually, those tons of science books and magazines so prized by Kuya Obet and I, even with the long-distance influence of our late Manang Willie, were not enough to provide us with a clue about the growing role of women in that “esoteric” field. Now I know more, thanks to the women’s liberation movement and the Internet.

Much respect to all women who still need to fight and win their battles, and not be sidelined, on the very frontlines of the sciences.

###

I wrote the above piece as a reaction to the following Facebook post (31 Aug 2025) by Johnny Linehan, on the near-forgotten role of Jocelyn Bell in the discovery of pulsars:

In the cold winter of 1967, deep in the English countryside, a young woman sat alone among cables and humming machines, her eyes fixed on squiggly lines of radio data.

Her name was Jocelyn Bell, a 24-year-old doctoral student at Cambridge. For months, she had helped build a massive, homemade radio telescope, and now, she was sifting through miles of printouts, searching for distant quasars.

But what she found was something entirely unexpected.

A signal. Faint, rhythmic, and impossibly precise. It pulsed every 1.337 seconds—so steady it seemed almost artificial. For a moment, the team jokingly dubbed it LGM-1, for “Little Green Men,” thinking it might be a transmission from extraterrestrial life. But Jocelyn didn’t buy into the alien theory. She was convinced by science, not speculation.

With tireless determination, she worked, ruling out interference, rechecking the data, and chasing the source. What she ultimately uncovered was extraordinary: a neutron star spinning rapidly, emitting radio waves like a lighthouse. It was the first pulsar—a discovery that would go on to be one of the most groundbreaking in astrophysics.

However, when the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded, Jocelyn’s name was absent. The honor went to her male supervisor, Antony Hewish, and Martin Ryle. Jocelyn said little at the time, though later she remarked, “It would demean Nobel Prizes if they were awarded to research students.”

But while the Nobel committee overlooked her contribution, history never did. Jocelyn Bell Burnell continued to shine as a guiding light in the scientific community—teaching, mentoring, and quietly changing the field of physics from within. In 2018, when she was awarded the $3 million Breakthrough Prize in Physics, she didn’t keep a penny. Instead, she donated the entire amount to support women, minorities, and refugees pursuing physics.

Jocelyn once said, “You can be good, or you can be lucky. I was both.” But the truth is, she was not just lucky—she was brilliant, persistent, and brave enough to listen when the universe whispered.